II.Kuyper’s world

Dutch parliamentary history starts in 1848, so that’s where

this historical overview also starts. In this article we’re going to take a look

at the 19th-century ruling group, the liberals, their challengers, the protestants,

and their struggle, the Antithesis.

Dutch political history until 1918 is mostly the story of, first, the struggle between

liberals and conservatives on the nature and interpretation of the constitution, and, after

that, the struggle between the victorious liberals and the protestants on the latter’s wish

to constitute a “sub-society” within Dutch society as a whole (with the state

footing the bill).

Leader of the protestants was the indomitable Abraham Kuyper, who, more than any other

individual, has shaped the structure and workings of Dutch politics.

During these struggles the catholics were the rather passive allies of first the liberals,

and later the protestants.

Protestants and catholics

The map shows the 1849 situation, which isn’t that different from the 1600

situation. The green areas are predominantly catholic, the red

ones predominantly protestant. Population was concentrated in the west, and the northern

provinces, especially, were thinly populated.

When the Netherlands achieved national independence in the late 16th century, the struggle against the Spanish

oppressor was waged by a motly coalition in which the members of the newly-established Dutch Reformed

Church played an important role.

As a result, the new Dutch state became nominally reformed, and only members of the Reformed Church were

allowed to hold political office. Officially the Dutch Reformed faith was the only legal one, but

in practice catholics, Jews, and members of the small protestant denominations were allowed to exercise

their faith as long as they weren’t too obvious about it.

The borders between catholic and protestant were drawn in the 1590s. In that time, the Reformed

had conquered state power in the newly-minted Netherlands, while the former Spanish overlords, who

occupied about one third of the territory that is currently Dutch, remained wed to the catholic cause.

In those days religious confusion was widespread; it was not unusual for one village priest to

dispense both catholic and protestant rituals. The two churches were not amused and started

up a conversion programme.

The catholics were more efficient, and they had tradition and the power of the state on their side.

Thus the southern provinces and some enclaves in the east which were occupied by the Spaniards around

1600 are still catholic.

The protestants were more circumspect; they didn’t want a second religious front in their rear

while struggling for independence, and there was always a gap between the hard-core calvinists and

the more moderate ruling classes. Besides, in many villages and towns particularly active

catholic priests, sometimes supported by the local catholic nobleman, kept their flock loyal to Rome.

Thus, while the south is uniformly catholic, the north became more of a patchwork, with the protestants

dominant, but with many pockets of catholicism.

The two southern provinces of Brabant and Limburg were conquered in the 1620s and 1630s, and by then

had become uniformly and stubbornly catholic. The fact that they weren’t allowed representation in

the States General and were ruled by northerners only strengthened their faith.

After the 1795 revolution

catholics, other protestants, and Jews were emancipated. We can safely forget the latter two groups,

who have never played an important role in politics. The catholics, though, are vital to understanding

the Dutch political system.

Despite this formal emancipation political power remained in the hands of the old Reformed

aristocracy. These rulers rarely called themselves protestants in a political sense, though.

Their faith played a minor role in their political actions. Instead, they divided themselves in liberals

and conservatives, with the latter supporting royal prerogative and the former the newly

emerging power of parliament.

Liberals and conservatives (1848-1878)

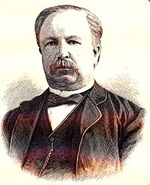

Johan Rudolph Thorbecke (1798-1872), creator of the constitution of 1848, prime minister

1849-1853, 1862-1866 and 1871-1872.

Originally a lawyer, Thorbecke became an MP in the pre-1848, indirectly elected parliament. He was part of the small

liberal opposition against the conservative, royal government, and in 1844 published a proposal for

revision of the constitution. Although this proposal failed politically, it caused a stream of publications

and an increased interest in constitutional matters.

His heydays came with the constitution of 1848 and his ensuing prime-ministership.

After his fall in 1853 he was twice more called to lead government, and in between usually sat in parliament.

Parties didn’t exist back then (and Thorbecke wouldn’t have liked them), but it’s best to see him

as the leader of the liberals. After a generational change in the 1860s he became the leader of the old liberals,

who were opposed by the young liberals.

1848 was yet another revolutionary year. Starting, as usual, in France, where the monarchy was

abolished for the second time, the revolution even spread to hitherto-safe bastions of conservatism

such as Prussia and Austria, and the conservative European system was tottering on the brink

of liberal anarchy.

Confronted with this unpleasant reality, King Willem II, who

had hitherto ruled as an all-but-absolute monarch, “turned from conservative to

liberal in one night” and called on liberal leader and eminent lawyer Thorbecke to

create a new constitution along liberal lines.

The constitution of 1848

Thorbecke’s work is the starting point of the current Dutch constitution, and it

covered vital matters such as the position of parliament and King. Government would be responsible

for all acts of the King, and a law was only valid when, in addition to the King’s signature

a counter-signature of a minister appeared on it.

As to parliament, it was to be elected directly, in a district system, by the wealthiest

10% of the male inhabitants. The new constitution was a huge step forward from the previous

system, where elections were indirect and restricted to an even narrower group, and parliament

had little power.

Most electoral districts were double districts that delivered two MPs, and half of parliament

was elected every two years. One MP was supposed to represent 45,000 people, and because

population kept growing, parliament did, too. The electoral table was to be revised

every ten years or so, and this gave rise to enthousiastic gerrymandering of the constantly

changing electoral districts.

In 1849 Willem II died to be succeeded by his son Willem III, who

appointed Thorbecke prime minister (or rather, former; we’ll

get back to that below).

No-party system

These new ideas gave rise to an entire system of constitutional debates, and the main

political cleavage of that age was the one between the conservatives, who generally supported

the prerogatives of the Crown, and the liberals, who wanted more power for parliament.

It would be wrong to see the conservatives and the liberals as political parties in our

sense of the word. There was no party organisation (in fact, leading thinkers rejected the

party system as a whole), and whether a particular member of parliament was a liberal or

a conservative was sometimes hard to say. There were many moderates who voted now liberal,

then conservative, while others started out as liberals and grew more and more conservative

as they advanced in years.

Socially, all members of parliament came from the upper or upper middle class; there was

little difference between liberals and conservatives here.

The anti-revolutionaries

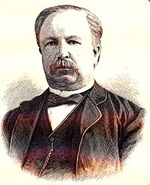

Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer (1801-1876), politician and historian, MP 1849-1857 and

1862-1866. He was

the first to speak out against the French Revolution and is considered the founding father of

the anti-revolutionary movement and protestant politics in general.

Groen started writing down his ideas in the 1830s. Basically, he held that the state needed

God as the font and origin of all authority; and that a state without God was unthinkable.

Although he acquired a moderate following, Groen remained a thinker more than a practical

politician. Besides, the concept of political parties hadn’t been invented yet, so he

he was unable to mobilise this following to gain political power even if he had been willing to do so.

Groen also played an important part in the writing of Dutch national history by his publication

of the correspondence of William of Orange, leader of the Dutch revolt of the 16th century.

Groen also popularised the view of the Dutch revolt as a protestant movement against the

catholic Spaniards.

The few members of parliament who thought primarily in a protestant frame of mind called

themselves anti-revolutionaries, and in the early years they were the orthodox right wing

of the conservative movement.

The anti-revolutionaries considered the French Revolution an affront to God and rejected the

theory of popular sovereignty, instead pointing to God and the Crown as the holders of natural

authority. Besides, they wanted faith to play an active part in politics.

In practice that meant the initial anti-revolutionaries (mostly party leader Groen van

Prinsterer and at most two or three henchmen) supported the Crown in its struggle with

parliament, placing them solidly in the conservative camp. In addition, the anti-revolutionaries

insisted on bringing the protestant faith back to the state-sponsored educational system. This

so-called “school struggle” would be a defining factor of Dutch politics for many

more years.

The anti-revolutionaries didn’t amount to much politically until Kuyper came around. It was Kuyper who

organised the loose and rather marginal anti-revolutionary denomination into a party.

The catholic emancipation

All southern members of parliament were catholic as a matter of course, and some northern

members as well. They occupied quite a few seats, but back then catholics were still second-rank

citizens, if not in name then socially at the very least.

Among catholic MPs, the concept of common action for bettering

the fate of catholics throughout the country was slow to emerge. On a modern left-right scale,

these catholic representatives were solidly reactionary. Still, they allied themselves to

the liberals, who, more than the conservatives, were willing to practice religious tolerance.

Catholic self-esteem was greatly boosted when in 1853 the Pope unilaterally restored

the episcopal hierarchy in the Netherlands, appointing solidly protestant Utrecht as seat

of the Dutch archbishop (as it still is today).

Thorbecke and the liberals did nothing. Their constitution guaranteed freedom of religion,

and if a certain church wanted to revise its organisational structure, that was an internal

affair of that church, and had nothing to do with the state.

This was a serious error of Thorbecke’s. The protestants, still the majority of

the country, disagreed vehemently with the Pope’s action, and especially his total

disregard for Dutch (protestant) history and sensitivities.

A wave of anti-catholicism swept throughout the northern provinces. The protestant

consistory of Utrecht took the initiative in requesting the rejection of the bishops, and

of the Pope himself by the Dutch state. This request was addressed not to Thorbecke’s

government, but directly to the King as protector of Dutch protestantism.

Royal prerogative

In an Amsterdam mass meeting the petition was given to the King, who replied that he

was unfortunately bound by the constitution and couldn’t help the protestants. This

response diverged sharply from the “humble advice” the government had given to the King

to point out the rights of the catholics, and call for religious tolerance.

In other words, the King had acted without government’s consent.

This is the crux of the liberal-conservative struggle that was to follow. How much independent

action could the King take, both in cases like the petition and in appointing a government

he liked?

The worst part was that according to the new constitution, government was responsible for these

royal acts. This created an impossible situation of a government divided in itself, with the

King taking one action and the council of ministers another. There

were but two solutions: either the King would switch to the government viewpoint, or he had

to appoint a new government.

Willem III decided to let Thorbecke go. Thus ended the first “liberal” government.

Still, the fact that three of Thorbecke’s ministers accepted appointment in the

subsequent “conservative” government shows that these party labels do more

harm than good.

Thorbecke personally was too liberal and too pro-catholic to go on ruling, so

Thorbecke personally had to go. Politics were personal in those days.

The Heemskerk governments

Jan Heemskerk (1818-1897), member of parliament 1859-1864 and 1869-1873, interior minister and

prime minister 1866-1868, 1874-1877, and 1883-1888. He started as a moderate liberal,

but became a conservative leader later during his career.

In his first stint as interior minister, Heemskerk became the soul of the conservative

government that tried to protect royal prerogative (as well as its own position) from parliament.

He later admitted that the second disbanding of parliament was a mistake on his part.

After his resignation he returned to parliament and became the leader of the conservatives.

He wasn’t perfectly suited to that task, though, being a lousy speaker and hard

to cooperate with. Also, conservatism had gone out of fashion: in 1873 Heemskerk was defeated

by an anti-revolutionary.

He returned as prime minister in 1874, when the liberals were hopelessly divided. He

tried to negotiate in the school struggle by producing a compromise law, but after their 1877

victory the liberals voted his law down, and Heemskerk resigned.

His last government was his most succesful one. Again he had to negotiate between

liberals and anti-revolutionaries in order to pass the new constitution. In the end, after

careful manoeuvring, he succeeded. When the new-style 1888 elections returned a clear

christian majority, Heemskerk voluntarily resigned, thus setting a precedent that is followed

to this day.

In the end Heemskerk’s importance lies not in his politics, but in the constitutional

examples he set by his 1868 and 1888 resignations.

The Heemskerk era set the stage for the relation between government and parliament that we now consider proper.

Parliament could reject laws or budgets, and in general ministers to whom

that happened would resign. Occasionally a question was deemed so important that government

as a whole threatened to resign.

Governments didn’t resign after elections, but only after such an unsolvable conflict.

At that point, the King appointed a new former, who would create a new government and become

prime minister.

The King had another option: he could disband parliament and call new elections.

This is what happened when in 1866 the “conservative” Heemskerk government was criticised

for the recent appointment of the colonial minister as governor-general of the East Indies.

New elections were called, but during the campaign the King issued a proclamation that

called on voters to vote conservative. This was widely seen as a bad move, and, true to the

theory that government was responsible for the King’s deeds, the liberals mercilessly

attacked Heemskerk. The voters agreed: although the conservatives won a few seats the liberals

kept their majority.

In 1868 a foreign affairs conflict caused the Heemskerk government to step down, but

its resignation was refused by the King, and instead parliament was again disbanded

and returned unchanged.

This wasn’t going to work. If parliament would be disbanded every time it dared to

disagree with government, and the King refused to appoint a prime minister whose political ideas

were shared by a parliamentary majority, the country would be in a continuous state of election.

The new parliament again rejected the foreign affairs budget and government resigned again.

The King gave in; permanently, as it turned out. He appointed Thorbecke former, and the liberal

leader created a government composed of people who had played no part in the recent struggle, and

remained in parliament himself.

This battle confirmed the rule that government had to be supported by a parliamentary

majority at all times, and it significantly decreased the King’s power.

After the Heemskerk fiasco the conservative movement lost much of its impetus. Essentially

the conservative label dissolved over the next twenty years, with the seculars opting for the

liberal label while the protestants took to calling themselves the anti-revolutionaries.

The catholics change sides

In the mid 1860s the liberal/catholic alliance broke down into its constituent parts. The two

groups had never really belonged together; temperamentally, all catholic MPs belonged on the

conservative side of the divide, and it was only the anti-papism of the old-guard anti-revolutionaries

that kept the catholics locked in an uneasy alliance with the liberals.

The Italian situation made matters worse. The nascent kingdom of Italy threatened the secular powers of

the Pope. Dutch catholics were solidly behind the Holy Father, and even sent thousands of

young men to serve in the papal armies; something the liberals, who supported Italian nationalism,

were unable to appreciate.

The conservatives and anti-revolutionaries, meanwhile, sought to break the liberals’

power and could use the catholic votes. Therefore they struck an alliance in the

Heemskerk era.

When the Italians conquered Rome in 1870, the catholics called on government to take steps to

restore the Pope’s worldly authority, but the liberals refused. (The idea found no support

among the protestants, obviously.) Then the liberal foreign minister decided that, since the

Pope was no longer leader of a sovereign nation, a Dutch embassy at his court was no longer

necessary. This insult was the last straw. The catholics sort of naturally gravitated toward

the nascent anti-revolutionary party, and it was a long time before catholics and liberals

would cooperate.

And keep the embassy question in mind. It was to become important in the Interbellum.

Kuyper and his works

Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920), ARP founder and party leader 1879-1920, founder

of the Gereformeerde church (1886-92), prime minister 1901-1905.

Educated as a theologist and minister, he started out as a liberal Hervormde, but his flock converted him to a

more rigid, Orthodox stance, which eventually led to the Gereformeerde Kerk and the creation of the ARP.

Party leader since 1879, Kuyper was rarely to be found in parliament, preferring to lead the party

from outside as editor-in-chief of his newspaper De Standaard. He fully supported the first 1888

catholic/protestant government, and in 1901, when the formation of a second such government was contemplated,

it was clear that Kuyper would have to take part in it himself.

The 1905 elections were a referendum on Kuyper, which he lost. When, after the 1909 elections, a new catholic/protestant

government seemed inevitable, Kuyper was discovered to have given royal medals to ARP fundraisers. His

prestige never quite recovered from this shock and his active political career came to an end.

In 1874 the protestant minister Abraham Kuyper, a rising star in the anti-revolutionary

movement, was elected to parliament. He didn’t exactly flourish there; within two years

he was burned out by the parliamentary work and decided to retire. This turned out to be the start,

and not the end, of his political career.

More than a parliamentary politician, Kuyper was an inspired leader

of the common protestant people, as well as a gifted speaker, organiser, journalist, and pamphleteer.

He deployed his considerable qualities in the opposition against the new 1878 liberal

school law that was to the disadvantage of the christian (protestant or catholic) schools.

(We’ll get back to this “school struggle” later.)

Kuyper popularised his point of view through his newspaper, and he gained the support of the

lower-middle class, orthodox protestants, who enthousiastically followed him and considered him

their God-given leader against the heathen liberals.

Founding of the ARP

Although the law passed, Kuyper’s organisation was an astounding success. Based

on it Kuyper founded the first Dutch political party, the ARP (Anti-Revolutionaire

Partij; Anti-Revolutionary Party), in 1879.

The ARP was the first modern political party, with a party leadership (headed

by Kuyper), a party programme (written by Kuyper), and officially approved party candidates for

parliament. This superstructure was supported by newspapers and election clubs that spread

the anti-revolutionary word throughout the protestant part of the Netherlands.

Initially the party had little electoral success, partly due to the district system that was

used back then, and because voting rights were restricted to the upper and upper-middle

classes who preferred conservatives to anti-revolutionaries. Still, the 1888 election reform

helped a lot there.

Kuyper wasn’t content with the ARP, though. He also wanted his own church.

The Dutch Reformed Church

“One Dutchman is a believer, two Dutchmen are a church, three Dutchmen are a schism.”

One of the crucial points of the Reformed faith is that every faithful is allowed to interpret

the Bible for himself. Since the Dutch love to disagree about obscure issues that

an outsider hardly understands, this aspect of the faith fits the national state of mind quite well,

and heated arguments within the Dutch Reformed Church occur with depressing regularity.

Historically the Dutch Reformed Church has reacted to such arguments by being rather broad and inclusive.

Ideally, every Dutch Reformed, from the nominal church-goers who were essentially liberal to the

hard-core orthodox, should feel at home within the church, and although ministers and their

flocks might disagree on theological points, the church ought to have room for every one of them.

There was a political angle to this whole set-up. Almost all politicians called either “liberal” or

“conservative” were Dutch Reformed in name, and although they disagreed on a

great many things, they agreed on the fact that the church should play no role in politics

and should also unite all protestant Dutch.

Because the leadership of the church was formed by these self-same “liberals” and

“conservatives,” they had an easy time of controlling it and making sure that

the theological disputes were kept far from politics.

In other words, the liberal elite that had accepted the new school law was also the leadership

of the church that kept it broad and allowed heretic, liberal thoughts.

Kuyper’s new coalition of the poorer, more orthodox protestants objected against both

parts of this equation.

Hervormden and Gereformeerden

Due to the Reformeds’ desire to split

up and the Dutch language’s inability to come up with more

than a few synonyms for “Reformed Church,” the innumerable groups all have similar-sounding

names even in Dutch. In English it’s worse; part of the vocabulary is lacking.

“Hervormd” and “gereformeerd” both translate to English “reformed.”

Because there are some fairly important differences between the two I use the untranslated Dutch words.

Oh, and “kerk” is “church”.

In 1886, after several years of agitation, the Kuyper-led Gereformeerde Kerk split off from the

main church, which we’ll call by its Dutch name of Hervormde Kerk from now on.

This schism is by far the most important in Dutch history, mainly because the Gereformeerden, through

their political vehicle the ARP, were the first protestant group to organise themselves politically

in order to conquer the state and reshape it in their protestant image.

The theological disputes need not concern us. Suffice it to say that

the Gereformeerde church considered itself far more Orthodox than the Hervormden, interpreted the Bible

somewhat more literally, and gave local churches a higher level of autonomy.

Not coincidentally, that higher level of autonomy caused a higher level of split-offs, too. Nowadays

there are dozens of Gereformeerde churches, and to make matters even more complicated there are also

the so-called “Hervormd-Gereformeerden,” groups that sympathise with the Gereformeerden

but remain within the Hervormde church.

Thus, the protestants have always considered three the absolute minimum of parties they need in order

to represent themselves. That’s what makes the study of the protestant denomination so complicated,

even for Dutch.

The school struggle

This new, potent duality of Gereformeerde Kerk and Anti-Revolutionary Party enthousiastically

entered the school struggle, which was to become one of the defining factors of Dutch politics

for years to come.

In the early 19th century the Dutch state had set up a first-class system of state-subsidised

primary schools that was the envy of Europe. (Secondary schools and universities were distinctly

less good, though.) Because the country was so divided between catholics and protestants,

these state schools would be neutral. They’d pay attention to general christian values,

but would not repeat the teachings of a specific church.

One important point was Bible reading. Protestants are required to read the Bible for themselves

and form an opinion, while catholics are forbidden to do so and should leave it to their priests.

What was a neutral school to do?

Kuyper’s point was that the Gereformeerden should be allowed to

found their own school system, in which their children would be reared in the proper Gereformeerde

faith instead of the state-sponsored godless neutrality.

Now nothing prevented anyone from founding a “school with the Bible.”

It would even get some money from the national government, but the city and town government did not pay

for buildings and teachers, as they did for the public, religiously neutral schools.

Even extending the school subsidy programme to include the religious schools was within the realm

of the possible, but, said the ruling liberals, then government would also be allowed to set part

of the curriculum.

Since the Gereformeerden wanted to avoid having to teach dangerous novelties such as the evolution

theory, negotiations broke down here. Kuyper wanted state money without state oversight, and that

went too far to the liberals.

We will not treat all the interminable phases of the school struggle, or the many legislative

proposals or counter-proposals. Suffice it to say that the school struggle became the touchstone

of a vicious culture war in the Netherlands, with protestants and liberals taking opposite

positions that gradually hardened and became dogma.

Kuyper never allowed the school struggle to die down; it was his most potent political weapon for

close to forty years, and it made the ARP the leading party of the country, even though it never

was the largest one.

The Antithesis

The school struggle took on a new dimension when it was discovered that the catholics, too,

had problems with state school neutrality. In the 1870s catholics and anti-revolutionaries

started to support each other when confronted with the liberal demand for continuing

neutrality of state-subsidised schools.

This led Kuyper to formulate the theory of the Antithesis. Essentially, he saw all faith-based

political parties or groupings as natural allies against the secular liberals (and later, the socialists),

and he held that these parties should support each other in the spread of God’s word throughout

Dutch politics, as well as in the solving of practical problems such as the school struggle.

Thus, Kuyper created the catholic/protestant alliance. From 1888 to 1918 the protestant/catholic

block was opposed to the liberal block, and political power switched between the two. The

electoral reforms of 1918 brought the christian parties the absolute majority, which they lost

only in 1967. Catholics and protestants reacted by merging their parties into the CDA, which

to this day stands at the centre of any Dutch political calculation. Although the Antithesis

is all but forgotten as a political theory, its effects still rule Dutch politics.

In the 19th century the anti-revolutionaries were the clear leaders of the christian

movement; although the catholics in fact had more seats and demanded a few ministers in any christian government,

it was the ARP that steered the alliance as a whole through its struggle with the liberals.

Denominational segregation

“Denominational segregation” is the non-literal translation of

Dutch “verzuiling.” This word literally means “pillarisation,” which is ugly English.

The underlying idea of Kuyper’s actions was that Gereformeerden (and, by extension, any

group) would have the right to organise their own society within the larger whole of Dutch society.

This was the true meaning of his founding of the ARP, the Gereformeerde Kerk, and his insistence on

separate schools for protestants (as well as catholics).

In this spirit Kuyper founded

protestant newspapers, a Gereformeerde university (the Free University in Amsterdam),

trade unions, social and sports clubs, and any kind of organisation that protestant people might

conceivably need.

Kuyper’s creation of the anti-revolutionary mini-society was so succesful that the

other political denominations followed his example. As a result, from about 1900 to 1970 Dutch society was split

into four “pillars,” one each for the socialist, catholic, protestant, and liberal denominations.

Separate

The broadcast question of the 1920s is an excellent example of how denominational segregation

worked in practice.

In 1923 a private company started the sale of a revolutionary new product: radio sets.

The chief sales officer was quick to point out that sales would soar if buyers

could actually listen to something on their new purchase. Therefore the company started

broadcasting radio from its corporate headquarters in Hilversum, near Amsterdam. It founded

the first Dutch broadcasting corporation, the AVRO. Broadcasts were commercial; anyone who

wanted to buy time on the radio station could do so.

This, now, was a danger to the denominations. Although the AVRO presented itself as non-denominational, that

was quickly equated with liberal, and devout, hard-working protestant, socialist, or catholic

people might get the wrong ideas from listening to such a radio station.

A year later the protestants founded their own NCRV broadcast corporation, which rented time

on the AVRO station. In 1925 the catholics founded the KRO and the socialists the VARA. Thus

all denominations now had their own radio station where only safe, approved programmes were

broadcast.

Still, the situation was not ideal. Therefore NCRV and KRO combined to create a new broadcasting

station which each of them would use for half of the time. Thus, the faithful would not be exposed

to secular programmes if they happened to turn on their radio set at the wrong time.

Besides, it allowed the catholic priest and protestant minister to easily check what their flock

listened to: in order to listen to liberal or socialist broadcasts people would have

to move the dial to the “wrong” position.

Thus the Antithesis was reinforced, and the catholic/protestant alliance had once more

defeated a sinister secular plot. The socialists were happy, too. The only loser was the AVRO,

whose idea had been to form a truly national broadcasting corporation.

In 1930 government approved this scheme of things, and the socialist/liberal and catholic/protestant

radio stations were officially sanctioned. It would take until 1965 before the broadcast question

was revisited, and then it caused the fall of government.

Broadly speaking, each of the four “pillars” had its own mini-society within the greather whole

of Dutch society.

Protestants read protestant newspapers, listened to

the protestant broadcasting corporation, were members of the protestant social club and the protestant trade union, bought at protestant grocers,

and sent their children to a protestant school, a protestant youth camp, and a protestant football club (which

did not play on Sundays).

According to a popular (though possibly untrue) story, the question whether goats owned by a catholic

farmer could mingle with goats owned by a protestant one was hotly debated. If any offspring occurred, which

faith would it have?

Mixed marriages were frowned upon, but they rarely occurred because there was no need to meet members of

another denomination. From cradle to grave, life was organised around the denominational structures that

kept the Dutch safe in their “pillar.”

Obviously, the system also had a political component. Each denomination had its own parties, and a faithful

member of a denomination would vote for one of them.

The four denominations

As a result, Dutch politics, too, came to be divided into four denominations. The catholic and protestant ones were locked

in an eternal alliance, to which some liberal or socialist parties were occasionally admitted — or excluded.

The protestant denomination is the model for the others, and it is the only one of which a tiny

sliver has survived the turmoil of the seventies.

The catholics had the immense advantage of being part of a highly organised church that could

easily copy the anti-revolutionary ideas. At the height of segregation, the catholic denomination

was the most advanced one, since it had the most total grip on its people, and, contrary to the other three,

had only one party.

The socialists, too, stole a leaf from Kuyper’s book. When the SDAP was founded in

1894, it quickly founded its own societal structures with newspapers, trade unions, social clubs,

and so on. Party leaders fondly commented that some workers filled in “Faith: SDAP” in the

census.

The liberals protested against this split-up of Dutch society.

Unfortunately, on this issue they found themselves massively out-voted and out-organised by all

other denominations.

Although the liberals maintained that they did not form a separate denomination, and preferred to

see themselves as the “neutral” or “general” stream within Dutch

society, the fact that catholics,

protestants, and socialists maintained their own, closed mini-societies in which liberals were

not welcome meant that there was little choice but to form a liberal denomination.

Of the four the liberals always remained the worst organised denomination. They lacked trade unions and

a broadcasting corporation, and in general didn’t play the command-and-control game with as much

zeal as the other three. It was less necessary; the liberals had no popular masses to educate, they

all came from a solid middle class or higher background.

Voting rights and school struggle (1878-1894)

Johannes Tak van Poortvliet (1839-1904), LU minister of

Waterstate 1877-1879, interior minister 1891-1894.

Tak van Poortvliet started as a clerk for parliament, but became a member of this august

body in 1870. He was part of the LU’s left wing. His stint at Waterstate was not succesful;

when parliament rejected his proposal to dig a canal between Amsterdam and the Rhine, government

resigned.

In the 1880s Tak became one of the leaders of the liberal left wing, and when the liberals

gained a clear majority in 1891 Tak was generally assumed to become prime minister.

However, Queen Regent Emma appointed not Tak but Van Tienhoven former, because she knew the

latter personally and was afraid of making a mistake so early in her regency.

Van Tienhoven accepted, but understood where the real power was located and invited Tak to join

him. Tak accepted on the condition that he become interior minister, that suffrage extension

would be a major spearhead of the new government, and that if the extension were rejected,

parliament would be disbanded and new elections held. Van Tienhoven and the other ministers

accepted this ultimatum without informing the Queen Regent.

When Tak unveiled his proposals they split the liberals and protestants, and a sharp discussion

ensued in parliament. A liberal MP proposed an amendment that he thought would bridge the

gap between pro- and anti-Takkians. He did not want to put Tak in an impossible

situation, and Tak seemed to indicate that, although he disliked the amendment, he would accept it.

Unbeknownst to parliament, Tak stated in the council of ministers that he would withdraw his

proposal if the amendment passed.

The amendment passed and Tak withdrew his proposal. Either Tak or Van Tienhoven should have

informed parliament of the consequences of accepting the amendment. When Tak now demanded the

disbanding of parliament, Van Tienhoven refused and resigned. Tak and the other ministers advised

the Queen Regent to disband parliament anyway, and the 1894 elections returned a clear anti-Takkian

majority.

The Queen Regent learned to make sure she was informed of all the negotiations and promises around government

formation; the fall of government had taken her completely by surprise. This has become a constitutional

rule.

Tak resigned from active politics and died broken and bitter ten years later.

Three political issues dominated the last years of the 19th century. In addition

to the school struggle they were the extension of voting rights from the well-to-do upper and

upper-middle class to the entire people, and solving the social issues created by the ruthless capitalist

oppression of the workers.

The third issue was slow to take root; parliament first needed an influx of left-liberals

and socialists before it began to be taken seriously. The school struggle and extension of

voting rights, though, were at the top of everybody’s mind.

The problem was that the catholics and protestants wanted their religious schools but

not necessarily an extension of voting rights, while the liberals wanted an extension of

voting rights but no subsidies for religious schools. And in order to change either a

revision of the consitution was necessary, and with that a two-thirds majority in parliament.

The 1877-1879 liberal Kappeyne government tried to change the school laws. All public

schools would be more heavily subsidised, but in return the state would have more influence

on the programme.

This was the proposal that Kuyper protested against and that led to the

creation of the ARP. In vain: the proposal was accepted, and despite a last-minute plea

from protestants and catholics the King signed the law.

Still, this battle had one winner: the modern party organisation, exemplified by the ARP,

but copied by the other denominations. Although the ARP remained by far the best organised

party until the rise of the social-democrats, it got increasingly stiff competition from

liberals and catholics.

Worse, it ran into internal problems. Voting right extension was a problem because the

Yes and No camps didn’t

conform to party lines. In general and as a matter of high principle the liberals were in favour

of extension, although some (former) conservatives wondered whether it had to be done right now.

The anti-revolutionaries were divided on the issue. On the one hand, many newly minted

protestant voters were expected to support the party, on the other hand the ARP, too, had

a powerful conservative wing that was led by Lohman, who was also the ARP’s parliamentary

leader. These conservatives were supported by the catholics, who rejected voting rights

extension.

The constitution of 1888

It fell to former prime minister Heemskerk, an old-school conservative himself, to form

a new government and decide on a moderate extension of the

vote based on property. This was more-or-less acceptable to the conservative liberals and

anti-revolutionaries.

Nonetheless, anti-revolutionaries and catholics now combined against government in order

to demand school equality in exchange for their support for the voting rights extension.

Heemskerk now tried to please the anti-revolutionaries, which

was rejected by the liberals, then tried to tack more in the liberal direction, which

caused the anti-revolutionaries to threaten to reject the entire new constitution.

In the end the electoral threshold became slightly higher than originally planned, and

subsidising religious schools was made possible (though not required). Thus amended, the

new constitution passed. Voting rights were now held by about 20% of the male population.

The number of seats in parliament was fixed at 100, all of which would be elected once

every four years in single-seat constituencies. The number of voters was roughly doubled.

The first christian government

Now the antithetical pendulum started to swing, with now a christian, then a liberal majority.

Due to the influx of new, middle-class voters, the catholic/anti-revolutionary alliance won the 1888 elections,

the first under the new constitution. Prime minister Heemskerk resigned because of this result;

and that was the first time a government decided the elections had been a vote of no confidence.

Heemskerk left politics, but his son Heemskerk jr. was elected for the ARP.

Based on the election results, a catholic/protestant government was inevitable. This

Mackay government added a little bit of subsidy to religious schools, but was rather

moderate all in all.

In 1890 King Willem III died, to be succeeded by his minor daughter, Wilhelmina. Her mother,

Queen Emma, became regent for the next eight years.

The Tak controversy

In 1891 the liberals reconquered the majority, and the left-leaning government decided to make serious work of

extending voting rights. To this effect, interior minister Tak van Poortvliet proposed legislation that basically

grante voting rights to any male who had a fixed abode and did not receive money from a charitable organisation.

The heated debate that followed caused the entire country to split up between pro- and anti-Takkians, who spilled

oceans of ink denouncing each other. The split ran straight through all parties.

The right-wing liberals split off from the main LU and founded the BVL.

Kuyper, who was only too well aware that his power rested on the support of the lower-middle class

Gereformeerden, not all of whom were entitled to vote, eventually declared himself pro-Tak. This caused the

anti-Takkian right wing of the anti-revolutionaries, led by parliamentary leader Lohman,

to split off and, after a series of mergers, found the CHU.

Thus the suffrage question split up both liberals and protestants. The catholics, as always, retained

their unity. For the moment they rejected extension of the voting rights.

Government fell over Tak’s proposals. The 1894 elections resulted in a clear majority for

the anti-Takkians. A right-wing liberal government was formed with some support from the catholics.

Thus the suffrage question had temporarily broken Kuyper’s alliance.

Continue

The battle between liberals and protestants was to continue for another twenty years. In addition,

the catholics began to organise themselves, and with the socialists an entirely new denomination

entered Dutch politics. All this gave rise to the bitter and partisan politics of

the Antithesis.