Yesterday I replied to a tweet by Marcos about “add to home screen,” and that kicked off a long and rather interesting conversation about installable web apps. This post gives my view.

As Bruce explained in his Fronteers 2013 session, bookmarking something in a mobile browser should mean adding an icon to the device’s home screen instead of making an entry in an otherwise undistinguished bookmark file. As soon as Bruce said this I knew he was right.

Like it or loathe it, consumers only take something seriously on mobile if they can install it, like they do with native apps. One of the often-quoted disadvantages of mobile web apps is that users get confused if they can’t download them and put them on their homescreen. So let’s copy the native experience here. From the user’s perspective it makes excellent sense. And while we’re at it, let’s call it “Install,” and not “Bookmark.”

So if you “install” this page on a mobile browser, an icon (probably my favicon, as long as I haven’t created a specific one) will appear on your mobile device’s home screen which basically serves as a link to this page, and the page’s title becomes the icon text.

How exactly should this work? I see two options. The icon could be a normal bookmark that contains the URL of this page. Tapping the icon would start up the browser and load this page.

But would a non-technical user expect this? I’m not sure. Therefore, the second option would be that the bookmarking causes a sort of “Save As, Webpage complete” where the page and its attendant styles, scripts, and images are saved to the device so that it can also be read offline. This takes a little more harddisk space, but not all that much, and it may be in line with what users expect. Slight technical difference: it would run in the WebView, and not in the browser.

It gets really interesting when you install not a static page, but a web app. (Let’s call it a web app for now. Something that functions as an app, is written in HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, and can handle some sort of offline use.)

Such a web app should be saved in its entirety, that much is clear. But how would the browser know what to save? And more to the point, how would it know that it’s trying to save a web app?

The solution is a manifest file. Personally I support the old syntax:

<html manifest="manifest.json">

When the browser detects this manifest file and is told to save the page, it’s the contents of this file that tells him which files to save, while the mere presence tells the browser this is in fact a web app.

I know, I know, this syntax is currently being used for appcache. So maybe we have to use a different attribute name. But a simple attribute on the HTML tag (OK, or a special <meta> tag, although I dislike them) is what we’re looking for. Besides, appcache is kind-of a foreshadowing of installable web apps (even though, as Jake points out time and again, it is really a douchebag), so maybe it makes sense to hijack its syntax.

Anyway. Some sort of special attribute points to a file that tells the browser this is a web app, and also which files to download. That’s the gist.

The elephant in the room is permissions, and this is what most of yesterday’s conversation was about. If the web app wants to access your location, or your address book, or your audio, you as a user should grant it explicit permission to do so. We do not want web apps that start by sending off your entire address book to a malicious server, after all.

Technically, permissions aren’t all that difficult. The user is asked to allow the app access to whatever it wants (one question per functionality), and can say Yes or No. Easy.

What’s not easy is the user interface. In fact, it’s bloody hard. First of all, some (most?) users won’t really understand what the question is. Second, the mobile screen is so small.

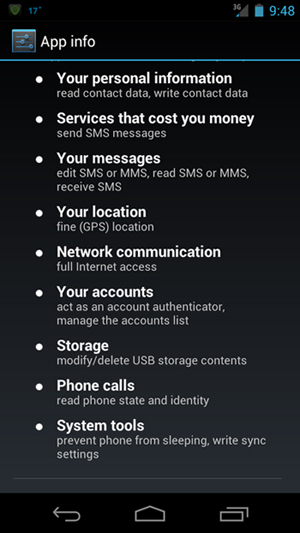

The Android way, which consists of listing all permissions you have to grant before the app will be installed and asking for one single Yes or No, does not work. It is a huge list, and users will not be able to make sense of it. So they’ll just say Yes in order to get on with it, and not really care exactly what they’re saying Yes to.

Asking for permission should be asynchronous. The question pops up, but the user is not required to answer it before continuing to interact with the web app.

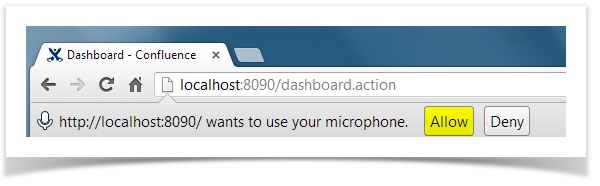

What comes close is the current desktop browser permission interface. A single bar with Allow and Deny buttons is created for every separate permission. So if the app wants SMS, microphone, and location permissions the browser shows three separate bars. (To be honest, I’m not sure if it works like that right now, but it should.)

True, these bars would still take up valuable real estate on a mobile device. I’m not sure if the bar model is the best possible solution, but it’s certainly better than an Android-style list of permissions.

Even if we solve the interface problem, we’re not done yet. When should the user give or withhold his permission? When the app loads? Or when it is installed? In fact, a large part of yesterday’s discussion was about exactly this problem.

First things first: once the user has given a certain permission he should never be asked again. So allowing microphone access means allowing it forever — though see below.

Still, when would the user expect to give these permissions? Yesterday’s disucssion was mostly about this question: at install time or at first run? After thinking it over I see a third option: at first load time.

Consider. Before installing a web app, it’s likely the user discovers it as a site and uses it a bit. During that use, it’s likely he already encounters a few permission questions and allows or denies a few things. These permissions, at least, do not have to be re-requested.

If any permissions are still undecided, I think we should ask the question at first run, i.e. when the user actually wants to use the web app and is ready to consider permissions again.

I see the installation of the app as the end of the discovery process. User finds web app online, uses it a bit, likes it, and decides to install it before going on to other things. This flow should not be interrupted by permission questions.

What’s also missing from most permission discussions (though not yesterday’s) is a third option apart from Allow and Deny: the “Dunno” option. It should be possible for the user to not answer a permission question at all. (This is one other way in which the Android model goes wrong: it requires a synchronous answer before proceeding to do anything. Ugly, ugly.)

Technically, Dunno is the same as Deny. As long as the user has not given explicit permission we do not allow the web app to access his address book. Simple.

Psychologically, though, from an interaction point of view, it’s different. The user honestly doesn’t know yet if he wants to grant access to his address book, or hasn’t come around to pondering the question yet, and the web app creator still has room to sway him — for instance by offering as much of the app’s functionality as possible until it needs the address book, and printing out a message like “If you grant permission X this app will be able to do Y.”

Therefore, apart from an onSuccess and onFailure event handler, any permission question should also have an Indeterminate logic branch. This is not only up to the browsers — web app authors should use the Indeterminate state in a logical and persuasive manner.

Finally, what if the user wants to change permissions? He denied microphone access, but changes his mind and wants to allow it, or vice versa.

I suppose that creating a special Permissions button, that opens a layer with the current permission status and buttons to change them, is not all that hard to implement. But would the user discover this on his own, and understand what he can do? Right now I don’t know, but this question needs an answer.

So. The mobile browser “bookmark” function should become “install” and place an icon on the home screen. This icon starts up the web page or web app; likely from local memory. Permissions should be requested asynchronously when the user is actually using the app, and they should be remembered for the app’s lifetime. Browsers and especially authors should make sure the Indeterminate logic branch is adequately covered. Finally, we need an interface to change permissions.

Once we have all that we’re a few steps closer to installable web apps that work like native apps from the consumer’s point of view.

And once we have all that we can start sending these web apps (or plain simple bookmarks) to other devices via some sort of P2P connection (Bluetooth, NFC, I don't care what). And once we've done THAT the mobile web will really start to take shape.

This is the blog of Peter-Paul Koch, web developer, consultant, and trainer.

You can also follow

him on Twitter or Mastodon.

Atom

RSS

If you like this blog, why not donate a little bit of money to help me pay my bills?

Categories: